During the summer of 2008, photographer Ham Bryan and writer Ruffin Prevost met with a dozen longtime residents of Cody, Wyo. Their goal was to learn more about the town's history from people who helped shape it, as well as to introduce — or reintroduce — those people to the current residents of Cody.

The intimate series of portraits offers a unique look at these dozen people of character, and the brief biographies share their memories, insights and advice on how Cody has changed, and how it hasn't.

Our thanks to those who sat for portraits and interviews. We hope you enjoy the end result as much as we enjoyed the process of creating it.

Elijah Cobb

Elijah Cobb

Elijah Cobbborn July 13, 1950

Photographer Elijah Cobb may be the only person ever to spend more money on housing in Cody than in New York City.

"I had incredibly low overhead there," Cobb said. "My apartment was $150 a month," and he worked in a darkroom in the basement of a building a few blocks away.

Since moving to Cody in 1995, Cobb's overhead has risen. He co-owns a home, a mountain cabin and Stone Soup studios. But he still aims to keep his overhead low, particularly when it comes to the power bill.

Cobb and Linda Raynolds were the first in Cody to spin their electric meter backwards, using solar panels to power Stone Soup studios. He has also installed a solar water heater, and even a makeshift passive solar chicken solarium made from double-paned sliding glass doors.

Chickens are frequent subjects in Cobb's work as a photographer, including photos that have a distinctly painterly quality, using the interplay of color and light to portray the natural world in surprising and unexpected perspectives.

His photos use colored gels, strobes, sunlight and unique techniques developed from years of playing with light.

Last winter, a season Cobb calls "studio time," he shaped a giant lens from ice, using it to focus the sun's rays and start a fire.

"I enjoy that quiet community time in winter," he said, calling those months one of his favorite things about life in Cody.

Cobb worked as a fine art photographer in New York, and supplemented his income printing photographs and doing commercial studio photography.

He continues those pursuits here, but said he misses a group in New York known as the Photo Salon, where he and other members would discuss and critique non-commercial photographic work.

"I miss the everyday assumption and acceptance that diversity of everything in life is good," he said.

But Cody has changed in the dozen years since his arrival, Cobb said, with more art galleries opening and more artists and photographers coalescing around its limitless natural beauty.

Though he misses the anonymity of big city life, Cobb said he is also sensitive to the changes growth has brought to a place like Cody, adding that focusing development near existing cities and towns is key to preserving the area's unique qualities.

He advises newcomers to "be involved in the variety of ways to make a living and get by."

"The monetary side is not the only side. It's getting an elk for your winter meat supply, or exploring all the ways you can do for yourself and barter with your neighbors to get by and increase your interdependence with your community," he said.

Cobb's life and work continue to revolve around chasing light amidst nature during Wyoming's abundant sunny days.

"It's the combination of photography and the style of work I do, where I deal with light and passive solar power, the capturing and excluding of sunlight...or a lens made out of ice where you start fire," he said. "Those things all work together in some strange way. That's what life is all about — playing with light.

"And Wyoming is good for that."

John Darby

John Darby

John Darbyborn June 12, 1932

A few years ago, a big-shot came to stay at the Irma Hotel, where most of the big-shots and regular folks who visit Cody stay at one time or another.

John Darby, owner of the hotel, doesn't remember the big-shot's name, but does remember why the man came to Cody.

"He said the reason he loves Cody was it reminds him of the town he grew up in. Well, that's the same for me," Darby said.

But that place, Boulder, Colo., is hardly recognizable anymore to Darby, whose family ranched there. He lived in a community of just a few thousand when he left about 30 years ago. Now, Boulder is home to 100,000, and Boulder County has more people than half of Wyoming.

So it's not much of a surprise when Darby says he hasn't seen Cody change that much since he has been here, first taking over the Irma Hotel in 1982 in a trade for his ranch on the Greybull River.

The lesson from Boulder is that change is inevitable, he said, and development is bound to come.

"You can't stop them. You can only make them do it right," he said.

One thing Darby figures he has done right is market the Irma, built by Buffalo Bill Cody in 1902, and where the showman kept a personal office and two suites, calling it "just the sweetest hotel there ever was."

Darby has always used the iconic western showman to attract guests. But he recalls how another top Cody tourist attraction spent thousands to find out how to market to visitors.

"They said you should do three things: advertise Buffalo Bill, Buffalo Bill and Buffalo Bill," he said.

"Maybe 15 or 20 years go, they did a survey in Europe of the most remembered American. It was still Buffalo Bill," he said.

"We just run it the way that Buffalo Bill ran it," Darby said of the Irma. "He got along with everybody."

Even when that means answering inquiries from tourists on their first trip West that some people might categorize as "stupid questions."

"Years ago, there was a lady that asked what time they turned the animals out in Yellowstone," he said.

And it's the animals — hunting, fishing — and the great outdoors that make Cody a wonderful place to live, Darby said. But it can be a tough place to earn a living.

His advice for those just graduating high school in Cody: "I'd tell them to go off to school and don't come back. There's no opportunity here, unless you're ready to make beds."

And as for Darby's own legacy as a Cody businessman?

"My credit's good," he said with a smile.

Alice Fales

Alice Fales

Alice Falesborn Sept. 29, 1923

When Alice Fales was growing up on Sage Creek, east of Cody, plenty of people still used horses to get around, and she wouldn't mind if that were still the case today.

"I remember I used to always ride my horse to town for the Fourth of July," she said. Riders would leave their horses at the livery stable on Beck Avenue, near where the Cody Auditorium is today.

"My sister never could hang her knees tight enough to stay on bareback. But then, I could never ride a bicycle and she could," she said.

Fales said she preferred when Cody was "more of a horse town," and residents adopted a slower pace, taking time to engage each other.

Later, she lived in Powell, and got a Valentine's Day visit in 1941 from Glenn Fales, who rode his horse from Garland to bring her candy. The two had been courting for about a year, and Glenn's romantic gesture sealed the deal. They were married three days later.

Alice and Glenn worked at farming and ranching near Sage Creek and Meeteetse, and Glenn made a name as a horseman and rodeo rider. Then, Glenn told her he had a chance to run a grocery store in Meeteetse, a move she still finds puzzling.

"Glenn was always a horseman. I couldn't believe when he said he was going to run a grocery store. He could hardly go buy a loaf of bread," she said.

"We never gave credit, but if someone wasn't able to get what he needed, Glenn would say, 'Here. Here's $20, go get what you want.' And that's how we made some good things happen."

In six years, only a single customer wrote a bad check, and that was for $5, she said.

Eventually, they were contacted by the Dawson family, who had owned a Safeway grocery store, but later bought the Rimrock Ranch, a guest ranch at the eastern edge of the Shoshone National Forest, along the North Fork Highway.

The couples made the logical move of trading properties in 1955. Alice and Glenn's son, Gary Fales, still runs the ranch with his wife Dede.

Though Glenn was a respected outfitter, Alice was as handy with a rifle as she was steady in the saddle, and wears a unique piece of jewelry that proves it.

A bear was caught helping itself to the goods in her hunting camp kitchen. It came back later and she put a stop to the shenanigans. Permanently. The old bruin's claws now adorn a striking necklace she earned the hard way.

The bears still wander the wilderness, and Cody has grown as Fales never imagined while one of about 15 kids attending school in the Sage Creek Community Hall, which her grandparents built.

"We knew just about everybody in town. To me, it's an honor to be from Cody and Sage Creek," she said.

Asked if she had advice for people starting out in Cody, Fales said, "Make friends!"

"We used to know everybody. Now you're just sort of a number. It used to be, even if you didn't know someone, you would stop and speak to them on Main Street. You always acknowledged them when you passed them," she said. "I miss that."

Val Geissler

Val Geissler

Val Geisslerborn Sept. 19, 1939

Though Val Geissler is highly sought as a Western entertainer for his guitar playing, singing and cowboy poetry, he doesn't consider himself the focus of his performances.

"I just happen to be the person on the stage. The real stars of the show are the people in the audience," said Geissler, who makes a point to turn spectators into performers while entertaining at dude ranches, conferences and other events.

Geissler uses costumes and props to help him portray wild characters, donning an old hat or a wooly robe to draw audiences into a richly detailed world of song and verse.

"I grew up dreaming of being a cowboy, and that's all I ever really wanted to be," he said.

But he doesn't just portray a cowboy. Geissler has lived the cowboy life, training horses, riding in rodeos, running ranches and leading backcountry trips.

Born in San Francisco, Geissler studied ranch management and animal husbandry at Cal Poly San Luis Obispo, and first came to Cody about 25 years ago to perform at the Buffalo Bill Historical Center. He liked the area so much, he moved here.

"I think this is the greatest outdoor backwoods wilderness portion there is in the continental U.S.," he said.

"I love the mountains. I love being in there," said Geissler, who works leading crews to control invasive weeds and also guides pack trips for private clients.

Geissler said he prefers the low-tech approach in the woods, eschewing many of the gimmicks and gadgets that some guides and many campers like.

"I'm still a rope, leather and wood type of a guy," he said.

"I'm an old fart, and I'm antiquated. Some people go into the backwoods and they want satellite phones and all that stuff. If you go with me and you die out there, you die out there. And if I die out there, I couldn't die at a better place," he said.

If he had a chance to go back and do things over, Geissler said he would still pursue a life in the rodeo, despite the serious injuries he sustained in the sport.

"If I had a choice, I would try to go and be a world champion saddle bronc rider," he said.

"I wouldn't trade a lifetime of sitting in the stands watching rodeos for one time climbing down over one of those rascals, nodding at the gate and waiting for it to open," he said.

Geissler said he understands why many in Cody want to see the town continue to grow, but cautions against runaway development.

"Contrary to popular opinion, we have too much emphasis on economic development. What you're doing is taking Cody away from being the kind of old Wild West, Buffalo Bill Cody, cow-town atmosphere that it used to have," he said.

His advice to those looking to make a living here is simple: do what you love.

"Don't chase the dollar. If you take care of whatever it is you do, if you take care of business, the money will take care of itself. When you start chasing the dollar, you'll make a lot of mistakes," he said.

Mary Louise Greever

Mary Louise Greever

Mary Louise Greeverborn Oct. 3, 1921

"Cody is a great place to raise kids. I think that's it more than anything else. They can go any place and do anything, and there's no big danger, no problems," said Mary Louise Greever.

She ought to know, as part of a large family growing up in Cody since the early 1930s.

"There were nine of us all together. I was the fifth. I mean the fourth," she said, losing track for a moment of her own place among the five boys and four girls of Lloyd and Louise Taggart.

"It's crowded, but I wouldn't change it," she said of her big family growing up. "No one is concentrating on just you."

Greever was born in Cowley, and came to Cody when she was 10 years old.

"It was a big change. Cody seemed like a really big town when we moved up here. I was just overwhelmed with it," she said.

"My graduating class was around 50 or 60 people," she said, adding that the small school size tended to "limit the dating pool."

Greever's father was a contractor specializing in road construction who built some of the roads in Yellowstone National Park. He also owned the Two Dot Ranch, north of Cody, although the family lived in town.

"I never was particularly interested in the ranch, as such. I was kind of a city girl," she said, adding that she rode horses, but mainly to get someplace, and seldom just for fun.

"I'm not really a horse person. I think I'm about half afraid of a horse. I've just never been friends with them. A shetland (pony) is what we started out with, and they are just mean," Greever said.

Except for a stint in Washington state when her husband, Bill, worked as an electrical engineer for Boeing, Greever has lived in Cody all her life.

"Washington was so cloudy and rainy, it affected Bill's health. He couldn't stand it any more," she said of her late husband. The two were married for 63 years.

Greever said she has enjoyed volunteering around Cody, including working for 20 years as a docent at the Buffalo Bill Historical Center and also as a hospital aide.

There's not much Greever would change about Cody if she could, she said.

"There's too many tourists, but we can't get by without them," she said. "Otherwise, I think we're doing all right."

Harry Jackson

Harry Jackson

Harry Jacksonborn April 18, 1924

In 1956, Life magazine published a nine-page photo essay on a rising 32-year-old artist subtitled, "Harry Jackson Turns to the Hard Way."

Anyone who knows Jackson probably can't imagine a time when he took the easy way.

Around Cody, Jackson is known as an irascible artist blessed to express the grand dramas and compelling moments of the lives of cowboys, always with an infallible sense of the West.

Harry is an iconoclastic sculptor and painter straddling the worlds of realism and abstract impressionism, and whose works grace galleries from the Smithsonian in Washington D.C. to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in Manhattan, as well as the collections of Queen Elizabeth II, the Vatican and many others.

But it is the "Hard Way" of approaching his work, whether handling horses and cattle or sculpting and painting them, that brings a deep authenticity to whatever Jackson does.

"I quit my Chicago mobster family just after my 14th birthday, in April of 1938. Cody was a small town then but contains many more people since my arrival in May – more than I want," he said.

"Stay the fuck out," is Jackson's advice to those thinking of moving here.

But if you are here, stop by the Harry Jackson Museum on Blackburn Street where you will find a collection of paintings and sculptures evoking a dizzying array of influences from Jackson Pollock’s abstract expressionism, Remington, Titian, Goya and beyond.

Meeteetse was even smaller, and it was on its Pitchfork Ranch that Jackson and his lifelong friend, Cal Todd, first worked as cowboys in 1939, remaining devoted compadres until Todd died in 2003.

In 1942, at age 18, Jackson joined the Marines. In November 1943, PFC Jackson fought in the 76-hour amphibious conquest of Japan's heavily fortified Betio Island, Tarawa Atoll. There he sustained head wounds that caused grand mal epilepsy which still affects him. Fifty-eight years later, at the age of 77, Jackson entered psychotherapy to help cope with his lingering trauma, and a few years later, he found his beloved toy poodle, Fiona — a Celtic name.

"Fiona helps save my life, 'cause she is closer to mother nature than humans are," he said.

The two fly back and forth to Jackson's Italian home, where they spend two months each fall and spring.

He first went to Europe in 1954 to study Renaissance masters like Giotto and Donatello.

But Cody will always be Jackson’s base camp, where many of his acclaimed works are on display in the Buffalo Bill Historical Center and at his own museum.

Though the art world prefers its works neatly divided into ready-made categories, Jackson continues to choose the “Hard Way,” confounding critics by creating new categories and exploring uncharted paths.

He must be doing something right. Life magazine published its last newsstand edition in 2000. Eight years later, Jackson is still creating art the "Hard Way."

For any true master, is there any other way?

— text edited and altered by Harry Jackson

Beverly Kurtz

Beverly Kurtz

Beverly Kurtzborn oct 13, 1931

Most people who move to Cody come here because they fall in love with the town's natural beauty.

But it was a man who Beverly Kurtz fell in love with when she arrived in 1955. She met and married Don Kurtz, who is still her husband.

"It was not easy," she said of adjusting to life in Cody after moving from St. Paul, Minn. "It was brown, like it is, and I came from green, so that was difficult."

Kurtz said she also missed the anonymity of city life, and adjusted slowly to a small town where everyone knew each other.

She only meant to teach high school in Cody for one year during her college days, but Kurtz "found the right man" and ended up teaching physical education here for a decade.

"When I came, not all the streets were paved. It was really still a very small town," she said.

"Cowboy and oil man were the two cultures at the time, and those were the years of the bar fights," she said. "It was difficult being a woman at that time."

Teaching has changed since the 1960s, Kurtz said, adding that she didn't think her strict approach to discipline and high expectations of students would be well received by today's kids or parents.

Not that it was always welcomed 50 years ago.

"I asked things of the girls at school that met with great opposition from parents, like bring sweatsuits for physical education in cold weather," she said.

She heard from many irate mothers who thought it was inappropriate for young women to wear anything but dresses or skirts.

"Girls didn't even wear slacks to school then. It was really a different time," Kurtz said.

She also learned that fitting in with friends and neighbors in a small town took time and patience. Newcomers must participate in civic life before recommending changes, advice that still holds true today, Kurtz said.

"It's very easy to alienate people if you aren't careful," she said.

Cody is still a great place to live, but many people aren't sensitive to how they fit into their neighborhoods, she said.

"I'd like to see more of a sense of place, where people think more about their neighbors and neighborhoods," she said.

Through the Shoshone Alpine Club, Kurtz and her husband were instrumental in establishing the ski patrol in 1956 at Sleeping Giant, as well as a ski school there and in Red Lodge, then called Grizzly Peak Ski area.

"It was kind of just a group of young people that were going up there at the time, so skiing was just something we all did," she said.

Kurtz still skies downhill and cross-country, and though she hasn't skied at Sleeping Giant in years, she is anxious to see the hill reopen.

Though she never thought of herself as athletic, Kurtz was a skier and swimmer from an early age, and helping others learn to do both has always been important to her.

"I love teaching, so skiing has always been just another thing to teach," she said.

Jerry Lanchbury

Jerry Lanchbury

Jerry Lanchburyborn Nov. 9, 1930

Whether shoeing horses or ministering to convicts, Jerry Lanchbury has always worked to gain trust by showing he cares.

"With horses, you have to have a familiarity with them, so they have confidence with you," said Lanchbury who has worked as a local farrier for nearly half a century.

He was employed as a road and highway maintenance worker as his primary job, but Lanchbury said it is his work with horses that he has enjoyed, and still continues.

For the past 15 years, Lanchbury and others have visited with inmates in the Park County jail, helping organize Bible study courses and spreading the Gospel.

"We just go in and present Bible study to them, and as we go through it, they get more involved. They've got plenty of time in there to get involved in the Word and become a little more receptive, too," he said.

"When they come to faith like that, it's pretty rewarding," he said, adding that some may pay lip service to their religious epiphany, only to later fall back into their old bad habits.

"But if you can just get the seed planted, then down the line, even though they get out and maybe forget for a while, sometimes they come back around," he said.

That seed was planted in Lanchbury during a Billy Graham crusade in Cody, after which he began working with youth groups, and later in nursing homes, work he continues.

It wasn't where Lanchbury expected he might end up. He was born in Powell, where his father worked for the railroad and met his mother, who moved to Ralston from Kansas because "she was very scared of tornadoes," Lanchbury said.

Lanchbury's family established the Eagle's Nest stage stop between Cody and Powell in 1893, before either town existed. "It was a stop for all the freight coming up from Thermopolis and Meeteetse or down from Red Lodge," he said.

Lanchbury has lived through tough times, including trouble with the law as a young man, after he was "raised in the rough life around the rodeo game."

"Then, after all that, I came to the Lord and it was a changed life. I wanted to be an ambassador for the Lord and I have been blessed," he said, citing his wife Barbara, who died in 1999, as among his greatest blessings.

"She just had that heart of serving people and caring, and through her inspiration, brought me in, giving the glory to God and her faith. If I had half her faith I'd be doing well," he said.

Lanchbury still lives north of Cody, on land near Cottonwood Creek that his father homesteaded. He raises "just enough cows to pay taxes on." The town has changed over the years, he said.

"You knew each other a little better, and if somebody was in need, they would come up with a great amount of help in a crisis. Even just in everyday living, they were there for one another," he said.

Many of the old characters — local celebrities famous for nothing much — are gone too. "There were a lot of them by Shoshone Bank. There was a rail that went down the stairs where they were, and a lot of them didn't even drink, but they were there every day, and you saw them and everybody knew them," he said.

"There's something about Cody that just grows and stays with you when you leave, and you miss Cody, and all you want to do is get back to Cody. I'm blessed for being here and having a family here," he said.

Jim Nielson

Jim Nielson

Jim Nielsonborn April 2, 1931

Jim Nielson said his father, Glenn, gave him some good advice that has served him well.

"If you're going to pull a fast deal, you better make it a good one, because you'll have to live on it the rest of your life," Nielson recalls his father telling him. "He really believed strongly that you have to treat people fairly and honestly."

Nielson said he never got to know his father well until he worked for him at Husky Oil.

Glenn Nielson, a farmer and rancher from Cardston, Alberta, moved to Montana in search of work in the mid-1930s. He worked at a refinery in Cut Bank, and in 1938 bought the Park Refinery in Cody, building it into Husky Oil.

Jim Nielson spent three years in the Navy and worked for Husky, doing everything from roughneck work in Canada to learning marketing in Salt Lake City.

Nielson's family had a farm at the site of what is now the Olive Glenn Golf Course, named for his mother and father, and one of the family's many low-key philanthropic efforts that has benefited Cody, including Boy Scout and Girl Scout camps and Yellowstone Regional Airport.

Nielson recalls raising hay and peas on the golf course property, rushing each summer to harvest in time for peak prices from a Cowley vegetable cannery.

"Pitching green pea pods and vines is darn hard work," he said.

Ranching is becoming even tougher work in Wyoming, with competition from Argentina, Venezuela and even Florida, where the grazing season runs year-round, Nielson said.

"If you can break even around here ranching, you've done a whale of a job," he said, adding that he would follow holistic ranching practices if he were starting today.

"The world is changing so fast, you've got to be able to go with it. You've got to continue to learn," he said.

Nielson eventually became president of the publicly traded Husky Oil, serving until its sale in 1979. He now operates Nielson & Associates, a private oil and gas management firm where his son Jay also works.

"Cody is a good place to raise a family," he said, adding that "your children can't disappear in a crowd, and that makes them think twice about something before they do it."

Nielson advised young people in Cody to "take advantage of all the computers, TV and newspapers you can, and stay abreast of what's going on in the rest of the world," adding that a good communications infrastructure was critical for Cody.

"I also think you need to get out and see what is around this area," he said.

Building a winter economy is also key for Cody's future, Nielson said. He is working to revive the Sleeping Giant ski area as a community run facility.

"I believe strongly that it has the potential to be great winter economic development for Cody and the Bighorn Basin. The more I see of that project, the more excited I get about what I think we really can do," he said.

"I also think we need to have things for older people to do. You shouldn't stop learning, and older people are useful. We need to find things for them to do," he said.

Lucille Patrick

Lucille Patrick

Lucille Patrickborn April 23, 1924

Lucille Patrick wrote the book about Cody's early days. Literally.

"The Best Little Town by a Dam Site" looks at Cody's first 20 years, while her "Caroline Lockhart: Liberated Lady" examines another female writer whose roman a clef chronicled some of the town's most colorful early characters.

Patrick grew up on the Diamond Bar Ranch before later moving to the Belnap Ranch, both located along the South Fork of the Shoshone River.

A self-described tomboy growing up, Patrick still wears a colorful beaded vest that once belonged to her father, James Calvin Nichols, who in his youth worked as a professional wrestler as the "Candy Kid."

If Patrick seems a bit like one of the local characters she has written about, she's quick to point out that Cody today is a crowded city full of bland newcomers compared to its days as a haven for rough-hewn pioneers.

"Cody was a small town and it acted like one. Now it's gotten too big for its britches," she said.

"It used to be a place where you could walk down the street and meet 50 people and they all knew you, and they were of every ilk," Patrick said.

"Everybody knew everybody, and we used to have so many old guys not too long ago, who would come up to me on the street and embarrass my friends — rough looking old guys, and I would know them. They were great guys," she said

"It was a great town, but it has lost something in its growing up," Patrick said.

"My mother used to get upset with me because I knew the old-timers and drunks, and they were all my friends," she said.

Patrick said her mother made attempts to reform her tomboy ways, "but it didn't work."

"I took my mother riding one day. We had been insisting she go for a horseback ride," which her mother did not want to do, Patrick said.

"I got into a slough where it was kind of boggy, and the horse started going down. My dad was yelling at me, trying to tell me what to do, but my mother was hysterical," she said.

"The horse threw me off in the mud, which was kind of fun, but my mother never went on another horseback ride. She said it was just too dangerous," Patrick said.

Patrick learned about art and knitting, and her mother influenced her in other ways, she said.

While she enjoyed horses, the best way to get around was in her blue Pontiac convertible, Patrick said. Before that, there was her friend's Model T Ford, which was nicknamed "Shasta."

"Because she has to add oil, she has to add water, she has to push it up a hill," she said, adding that the only way the car would make it up the switchbacks in Sunlight Basin was in the lowest gear — reverse.

When asked her advice for newcomers to Cody, Patrick is quick with a one-liner: "Go back home!"

"But seriously, I think you have to become part of the town," she said. "If you think you're hot stuff or too good for everyone, you may as well go back home. That ain't the way Cody is, and it never was."

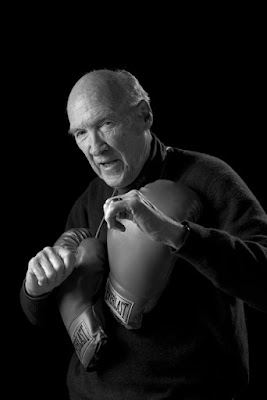

Al Simpson

Alan K. Simpson

Alan K. Simpsonborn Sept. 2, 1931

Al Simpson has had his share of bruising debates during 18 years in the U.S. Senate. But in politics, as in life, he has found there's more to be gained through compromise than conflict.

"Bob Rank was a guy from Cody who was a Golden Gloves boxer. He'd hit a guy, and the water from his hair would fly up and hit the lights and sizzle," Simpson remembered from his high school days.

Rank later was a two-time collegiate heavyweight champion boxer, but as a Cody High School student, he was the core of teacher Bill Waller's boxing program.

"'I'm going to teach you how to box,'" Simpson recalls Rank telling him.

"Well, I'd seen what he had done to the other guys — they would box him and come out with blood on their mouths," he said.

After much goading, Simpson put the gloves on and took Rank's advice to hit him as hard as he could.

"I thought it would be a terrific blow, but he just laughed," Simpson said. "So I brought another one right up from the floor and laid it under his chin and took off running. I was in City Park while he was still yelling, 'Come back. I'm not finished with you.'"

That was the extent of Simpson's boxing experience, at least inside the ring.

"It was a wonderful place to grow up," Simpson said of Cody, adding that there were "no paved streets" at the time, and around his family's house near the Episcopal Church, "there was nothing out there but a prairie dog village."

Those who came before him provided for the future — his future — Simpson said.

"Somebody built the red school and put me through high school. Somebody built those things for me and I don't know who they were, but I hope I will have done something for the next generation," he said.

He continues to champion the local school system, and can be counted on to serve as chairman (and be a personal backer) for just about any civic project aimed at boosting Cody's fortunes. "I'm one who loves to watch progress," he said.

It is perhaps because he lived in Cody at a time when there was so little that Simpson continues to work to give the town more.

"The thing about Cody that is unique is the young people want to come back. Not immediately. They want to get out of town, but they eventually come back," he said.

"There's a friendliness that's still here. You walk down the street and if you nod at somebody and say, 'Hi,' they will too," he said.

"People don't care who you are," he said, adding that everyone is treated equally.

The son of a Wyoming governor whose son is a leader in the Legislature said he is still stopped on the street and lectured about politics or asked about how he's recovering from prostate trouble six years ago.

But mainly, he said, the town forgives those who make mistakes and own up to their transgressions. That's something he learned first-hand at 17, after confessing to shooting mailboxes around town with a group of rowdy friends.

"There's always a shot at redemption in this town of great soul. They'll give you a second chance," he said.

Bill Smith

Bill Smith

Bill Smithborn June 28, 1941

"I love horses. I wouldn't want to be on this earth without horses. They're my life," said Bill Smith.

"I've seen some people I didn't like, and there's a lot of people that didn't like me. But I've never seen a horse I didn't like. And most horses, after they get to know me, they like me too," he said.

Bill Smith, or "Cody Bill Smith," as he was known on the rodeo circuit, grew up around horses and became a three-time world champion riding them. For a quarter-century, he has made a living in Thermopolis training and selling them through his nationally acclaimed WYO Quarter Horse operation.

Born and raised near Red Lodge, in the mining community of Bear Creek, Smith moved to Cody in 1958, before his senior year in high school.

"The first time I was ever in Cody was when we moved here," he recalled.

Smith said he was a "little scared" moving to the big city of Cody, after going to school in Bear Creek, where for the first eight years, "it was me and one other girl with the same teacher who taught every subject."

"It all seemed awful big to me. I was pretty much of a little hick," he said.

But at the Cody Nite Rodeo his senior year, Smith began his rise as a saddle bronc rider.

"It's as great a life as you can imagine for a young guy that's able to win enough money to live on," he said.

Smith was a world champion saddle bronc rider in 1969, 1971 and 1973, but was on the road 300 days each year.

"The rodeo business is tough on people," he said, adding that the time away from home led to a divorce from his first wife. "It takes a lot of sacrifices, and it's not for everybody."

"I've done some clinics and bronc riding schools, and the most important thing I've taught people is, 'This isn't for you.'" he said.

"If it was easy, everybody would do it. It's a fairy tale lifestyle, but it's tough to try to be the best in the world at what you do, even if you're shooting marbles. To make a living at it, you had to be in the top four or five," he said.

"It's still basically the same," Smith said. "The horses don't change."

But Cody has changed over the last half-century, he said.

"It's getting more Jackson Hole-ish, just growing bigger and busier. Everything is getting more metropolitan, and it's losing that local feeling. So many new people have moved in," he said.

"But it is what it is. Progress goes on, and you have to deal with it the way it is," he said.

"I'm not one to give anybody advice. I was lucky to get out of here alive myself," he joked. "But the advice I give every young kid is that whatever you do, keep your word. Do that and be honest and work hard."

Then he recalled his own time as a teenager, and figured that advice to young people is generally lost until they've found the same wisdom through their own mistakes.

"They're not going to listen to you anyway," he said.